News

COVID boosters are the secret to getting back to normal. Why are Americans so resistant to them?

WASHINGTON — On Tuesday, Denmark lifted all of its remaining coronavirus restrictions — a moment that millions of Americans have been longing for, especially as the Omicron wave that began in December appears to be subsiding.

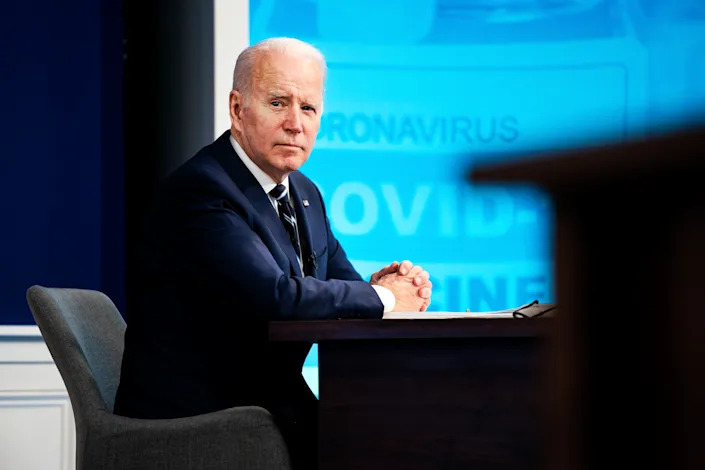

Recent polling indicates that pandemic fatigue is rising among ordinary Americans, a trend that elected officials have noticed. “We need to move away from the pandemic,” Gov. Asa Hutchinson of Arkansas said on Monday, after he and other governors met with President Biden.

Denmark is an enticing vision of what could be. So is the U.K., where coronavirus safety measures were dispensed with in mid-January. But neither the president nor his top public health officials have been eager to signal an end to the emergency phase of the pandemic by lifting any remaining federal restrictions or softening safety recommendations (such as in-school masking).

The reason is simple, the challenge intractable: The fast-moving Omicron variant is still causing more than 2,500 U.S. deaths a day — and not nearly enough vulnerable Americans have received their booster shots to prevent the next serious variant from taking a similarly tragic toll.

So far, despite an endless supply of shots and months of easy access, barely a quarter of the U.S. population (27 percent) has received a booster — less than half the Danish (61 percent) or British (55 percent) rate.

Even among Americans who’ve already received their initial vaccine doses and are eligible for another, nearly 50 percent have yet to get a booster, which offers much greater protection against serious or critical COVID-19 illness than what continues to count for full vaccination (two doses of the mRNA vaccines manufactured by Pfizer or Moderna, or a single Johnson & Johnson shot).

A new CDC study of the Omicron surge in Los Angeles found that while vaccinated people were 5.3 times less likely to end up in the hospital than the unvaccinated, boosted people were 23 times less likely to do so, meaning that boosters afforded four times more protection against hospitalization than a first-series vaccination alone.

The result is practically unique to America, where vaccination rates are solid but booster rates are low: “A pandemic of the unboosted,” as Dr. Peter Hotez, an infectious-disease expert at Baylor College of Medicine, recently told the Financial Times.

Since Dec. 1, when health officials announced the first Omicron case in the U.S., the share of Americans who have been killed by the coronavirus is “at least 63 percent higher” than in any other large, wealthy nation, according to a New York Times analysis published earlier this week.

“The only large European countries to exceed America’s COVID death rates this winter have been Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Greece and the Czech Republic, poorer nations where the best COVID treatments are relatively scarce,” the Times reported.

Experts say fading vaccine protection — along with higher numbers of unvaccinated and overweight residents — is a major reason why.

“What if there was a way to prevent 99% of Covid deaths and 96% hospitalizations, safety was validated in billions of people, it was free, and there was an unlimited supply?” Dr. Eric Topol, founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, tweeted Wednesday.

“There is. 3 shots,” he continued. “But tens of millions of Americans won’t go for it. And the US outcomes reflect that.”

Why is America so bad at boosters? The country’s initial vaccination effort was more or less successful, with 74.2 percent of all adults — and 88.4 percent of seniors — now considered “fully” inoculated, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But its subsequent booster effort has been hampered by regulatory disagreement, confusing public health messaging and the spread of misinformation, not to mention two new waves of the coronavirus since the fall, when the booster effort was just beginning.

“The White House COVID-19 team was correct back in August 2021 when they said that most Americans would need boosters and that the effort would begin in September,” Dr. Leana Wen, a former Baltimore public health commissioner, told Yahoo News. “But then the messaging became very convoluted from the CDC. The American public generally understood this back-and-forth to mean that boosters were a nice-to-have luxury instead of essential.”

The contrast with peer countries is stark. In a Twitter thread explaining Denmark’s decision, political scientist Michael Bang Petersen, who advises the Danish government and leads the country’s largest study of pandemic behavior, rattled off several key differences with the U.S. that have allowed his homeland to return to normal first.

But one data point in particular stood out. “Sixty-one percent of the [Danish] population,” Petersen wrote, has “received a booster vaccine.”

In Europe, that figure is hardly an outlier. More than half of Germans, Italians and Belgians have received an additional dose, and France, Spain, Canada and the Netherlands will soon clear the 50 percent mark themselves.

Yet Americans trail far behind — and that, more than anything else, is what’s holding the U.S. back from declaring an end to its own state of emergency, experts say. Some of the U.S. states with the lowest booster rates have already returned to something approaching normal, while more cautious blue states continue to wait, even as booster uptake remains anemic nationwide.

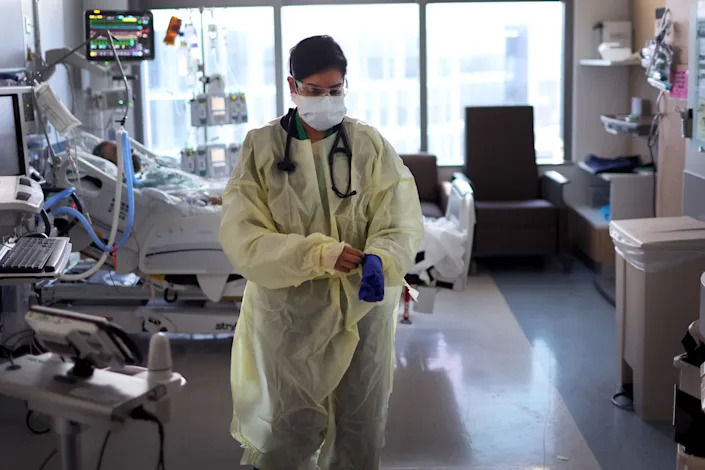

The disparity is startling, and the conclusion obvious. “The percent of people who are currently hospitalized due to COVID-19 are disproportionately unvaccinated and disproportionately not boosted,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky said on Wednesday during a White House pandemic response team briefing to explain why the U.S. has been slower than its European counterparts in returning to normal.

She shared a statistic from a hospital surveillance network: Only 8 percent of people age 65 and over who were hospitalized for COVID-19 had been boosted. “We really do have to look to our hospitalization rates, and our death rates, to look to when it’s time to lift some of these mitigation efforts,” Walensky said.

The science on boosters has been clear for months. Even before the hypermutated Omicron variant materialized last November, studies were showing that the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines’ original 90-plus percent effectiveness against COVID infection and hospitalization had worn off over time and in the face of the hypercontagious Delta variant — but that it could be restored, almost instantly, with a third shot.

Once Omicron materialized and started to spread even faster than Delta due to its superior ability to sidestep our immune defenses, this effect became more pronounced. According to several major studies summarized by Topol, two waned vaccine doses now reduce the chances of an Omicron infection by just 25 percent compared with no vaccine doses — while reducing the chances of hospitalization and death due to Omicron by just under 60 percent.

A booster, on the other hand, is twice as effective as two shots against infection (50 percent) and almost completely effective against hospitalization (90 percent) and death (95 percent), even after three months.

Clearly, booster shots are the surest way of keeping vulnerable people out of hospitals. And keeping people out of hospitals, in turn, is the surest way to return to normal, as Walensky said on Wednesday.