News

Fresh round of school closures tests Biden’s promise

WASHINGTON — Throughout the fall, the Biden administration touted its ability to open schools for in-person instruction in the midst of a pandemic. “Now over 99 percent of our schools are open,” President Biden said last month, drawing a contrast with his predecessor, Donald Trump.

But the Omicron wave of the coronavirus has challenged that promise, leading schools to close across the country. According to data site Burbio, more than 2,700 schools began 2022 either with remote instruction or with a day off.

Parents took to social media on Monday to lament the return of “Zoom school,” which in some cases was announced with little notice, while some educators said remote learning should continue for the near future.

“Go remote now and save staff, students and families,” the New York City-based educator Jennifer Gunn wrote on Twitter.

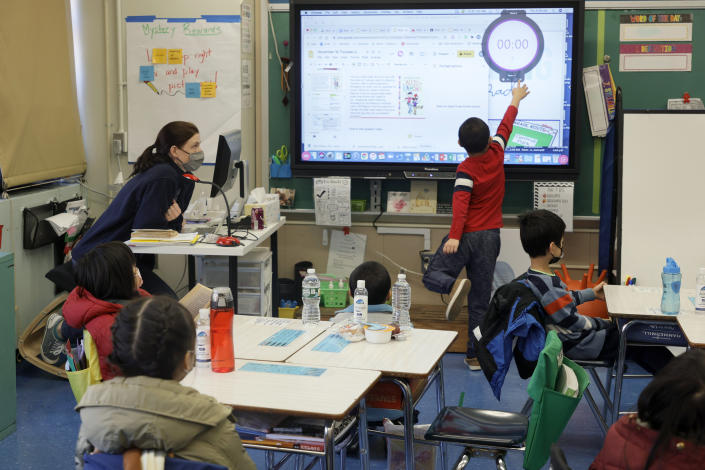

New York City has the nation’s largest school district and is generally seen as a bellwether when it comes to many aspects of educational policy. Students there returned to school on Monday, with the city’s new mayor, Eric Adams, vowing to keep kids in classrooms. “We want to be extremely clear,” Adams said on Monday while visiting an elementary school in the Bronx. “The safest place for our children is in a school building. And we are going to keep our schools open.”

It all amounted to yet another round of tumult and disruption for what some had hoped would be a more or less ordinary school year, which began with a bitter battle over school-based mask mandates precipitated by the emergence of the Delta variant. Just as a new pandemic normal appeared to finally set in during October and November, Omicron came along.

Despite the current disruptions, there are hopes that school closures will not be as prolonged or universal in the winter of 2022 as they were in the spring of 2020, when the coronavirus first arrived in the United States. For one, indications from South Africa and other nations suggest that Omicron leads to spikes that are sharp but brief, potentially lasting only several weeks.

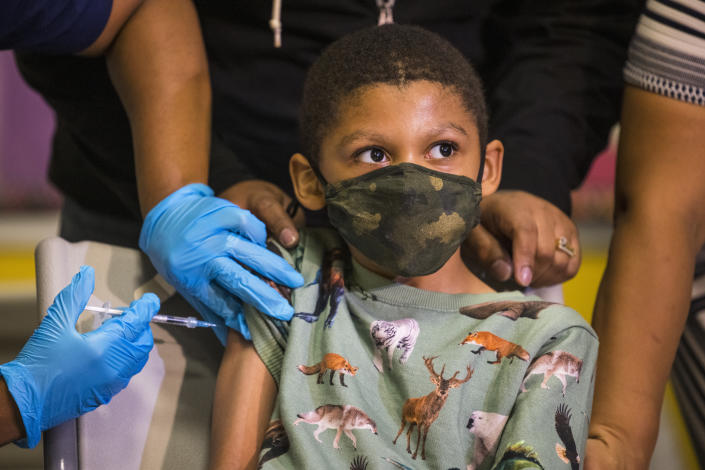

Omicron is more transmissible but less virulent than earlier strains; the variant has been in the United States since late November, leading to a dramatic rise in infection rates. Children are less likely to be vaccinated than older people, and the hospitalization of minors jumped in the second half of December.

Younger children have generally been safe from the most severe effects of COVID-19. The same remains true for boosted adults, despite a rise in breakthrough infections. But uneven vaccination rates, ever-changing mitigation measures and complex political crosscurrents have made for an inauspicious return to school, presenting Biden with a fresh challenge as he looks to project a renewed sense of competency.

Republicans were already making the new round of closures a political issue by Monday afternoon, plainly aware that it has particular traction with the suburban voters they hope to win back with a Trump-free platform later this year.

Administration officials told Yahoo News that they remained committed to keeping schools open safely for full-time, in-person learning. They also pointed to findings by the National Center for Education Statistics that 99 percent of secondary school students were going to school in person full-time, a figure Biden and other administration officials are fond of reciting. But that data comes from Dec. 15, and the situation has changed rapidly since then, especially as districts confronted the realities of reopening after the long holiday break.

Detroit administrators said on Dec. 31 that they were canceling school — with no remote option — until later in the week, out of a concern for “staff shortages due to positive and close contact scenarios.” Staff are expected to take a diagnostic test ahead of a Thursday return to the classroom.

Atlanta moved to remote learning over the weekend.

The reality was also evident in Washington, where Biden returned after spending the holidays at his Delaware beach house. Schools are closed until Thursday in the District of Columbia, with all students required to show proof of a negative result on a rapid test to return for in-person instruction.

Even so, educational officials there, and in many other parts of the country, are preparing to find cases in classrooms, leading to students and teachers having to isolate at home. “We expect that schools and classrooms will need to transition to situational virtual learning throughout the semester, especially in the coming weeks,” District of Columbia schools chancellor Lewis Ferebee told parents in a Dec. 29 email.

Schools in Newark, N.J., will conduct remote instruction for the next two weeks because so many educators have tested positive there. “COVID-19 continues to be a brutal, relentless, and ruthless virus that rears its ugly head at inopportune times,” Newark’s school superintendent, Roger León, wrote in announcing the closure.

Educational loss and social disruption aside, a fresh round of closures poses a risk to Democrats, who are already fearing dismal congressional midterm prospects. Parents furious at school closures helped Glenn Youngkin, a political neophyte, win the Virginia governorship, and the Democratic governor in solidly blue New Jersey was also nearly unseated.

Republicans believe they can use school closures to depict Democrats as overly cautious, insensitive to the needs of parents and beholden to teachers’ unions with increasingly progressive agendas. The longer closures persist into 2022, the easier that argument will be to make come election time.

“The science is on our side,” former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie told Yahoo News early last year, as Biden struggled to open schools that had in some cases been closed since March 2020.

The vast majority of schools did open last spring, and then again in the fall, even as the Delta wave swept across much of the country. Since then, some 23 million children under the age of 18 have been vaccinated, according to the CDC. But children have not been eligible for booster shots, an added layer of protection without which the Omicron variant shows the ability to cause a breakthrough infection (the Food and Drug Administration announced on Monday that adolescents were now eligible for boosters). An infected person still has to quarantine, even if they show only mild symptoms, making disruptions all but inevitable.

“There will probably be individual school closures, whether due to an outbreak, or not enough staff,” a San Francisco Bay Area education official told Reuters.

Despite his close alliance with the teachers’ unions, which in many cases continued to insist on remote learning even as studies showed that in-person schooling was safe, Biden has been at pains to demonstrate that he could coax educators into returning to the classroom without the rancor that marked Trump’s unsuccessful attempt to do the same.

Biden’s coronavirus relief package, passed last March, included $130 billion for schools, funds that were intended to make ventilation upgrades and other preparations for in-person learning. And in December, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced a new test-to-stay guideline, which uses rapid testing to keep students from having to undergo lengthy quarantines after coming into close contact with an infected person. Such quarantines led some schools to close for in-person learning throughout 2021.

But local control of education means that the president has little say in what individual states, let alone districts, decide. And though he has promised to rapidly increase the supply of rapid tests, their scarcity has made it difficult for many districts to implement the new test-to-stay guidelines.

Top administration officials have continued to insist that schools should open, given concerns about educational and social deprivation caused by having children learn at home. “It’s safe enough to get those kids back to school,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, the president’s top medical adviser, said on Sunday, “balanced against the deleterious effects of keeping them out.”

Yet the messy political and epidemiological realities are difficult to ignore. Speaking on the same day, Education Secretary Miguel Cardona conceded that there would be closures in the days and weeks to come, especially with millions having traveled in recent days, potentially leading to increased spread.